Digital Detritus

My first professional IT gig was in a data center. As a lowly (but paid!) intern from a local community college in their IT degree track, I was tasked with racking kit, triaging customer issues, and as my last task, assisting with the finalization of our new site just up the road.

In laymen terms, I was shoving servers onto rails, terminating cables to exacting specifications, and getting every last flake of dust out of a build site so new servers could move in.

Now to be clear, I loved that internship. The hum of power bars, the whirring of fans, the ability to adjust my climate by single degrees just by choosing which rack and aisle I stood in, it was glorious. So too was being rewarded for my perfectionism. My boss, a portly gentleman with a honest-to-god neckbeard, would cut any cable job that did not meet his exacting thermal and style standards, forcing the worker to start all over again. He did this to one cable of mine, one time, to fix a service loop I'd created by mistake; I never had a fuck-up ever again.

Author's Note: The downside of being consistently rewarded for perfection is disappointment in one's own lackluster work going forward, even if said work is perfect by the standards and tools you have available to you at the time. Alas, I do not earn enough to purchase a rolling tool case of Fluke tools and Belden cable for the odd wiring job.

Oddly enough, that job experience feels oddly prescient in the current era of AI and Public Cloud Compute, with datacenters sprawling across landscapes, gulping resources like water and rare earths while hastening climate catastrophe through the consumption of fossil fuels for energy. Most of my peers have never worked in an honest-to-god datacenter before, and are thus divorced from the means of (digital) production for their careers. To them, a datacenter is a magical, far away place, packed with racks of servers and kit to be consumed via API. Unless they're in a public cloud region with constrained resources, they have limitless capacity to grow, expand, experiment with - provided their credit card has available spend. When the core building blocks are abstracted away - processors, storage arrays, network layers, add-in cards, co-processors - it becomes easier to build, but also easier to waste.

In physical manufacturing, waste is a very real problem that must be dealt with immediately. Space is limited, as are funds, and so there's a very strong incentive to curtail waste early on and throughout the entire process. It's why manufacturing continues to chase the closed-loop supply chain, a holy grail of zero waste and infinite reuse of existing resources. Apple is arguably one of the larger names chasing this goal, seeing infinite dollar signs if they can capture the entirety of their waste and recycle it into new products for just the cost of energy and logistics alone.

In the digital space, waste isn't even in the lexicon of most organizations. Technology has always been measured by consumption and charged accordingly, the common belief being that data is infinite in its amount and reproducibility. Long before the modern era of Layer-as-a-Service (SaaS, PaaS, IaaS, AIaaS, etc), estates were judged by CPU sockets, memory capacity, rack units, power consumption, storage space, and network links. Billing was issued according to physical resource consumption rather than digital utilization, promoting consolidation of resources where possible and curtailing spend. After all, if your organization could only afford half a rack of colocation space, compromises would have to be made to ensure success.

With the service model and public cloud compute availability, consumption was no longer constrained solely by physical space, but by department budget. In Western companies especially, budgets are often "use it or lose it", meaning any unspent money at the end of the fiscal year is lost - and may even result in a downward revision of next year's budget. This is, definitively, a very bad way to deal with money, and the net result is a continuous expansion of the technology estate in line with available budget. Need to spend $50k before the end of the year? Sounds like the perfect time for a pilot project, maybe even one with a buzzword attached for good PR.

This, understandably, has lead to incredibly wasteful spending on outsized technology footprints. While it's definitely a boon to be able to separate dev from test from staging from production, organizations generally don't actually give a damn about return on investment until and unless there's an outside motivation for doing so - like activist shareholders demanding substantially higher returns on their (often very recent) investment. Bringing up cost reductions or monitoring voluntarily is often career suicide at an enterprise - speaking from first-hand experience. Nobody ever wants to save money, only spend ever increasing amounts of it because of the incentives to do so outweigh the benefits of prudent consumption, even - perhaps especially - for highly speculative projects or purchases with little to no chance of ROI. To raise your hand and suggest a modicum of restraint or common sense, is to out yourself as a threat to those whose political power is derived from budgetary shenanigans.

You knew AI was going to get a mention...

Which brings me to the sheer waste of modern technology. We don't just waste CPU cycles with inefficient code or squander rare earths on yearly product cadences, we have reached a point where a plurality of the technology industry as a whole is actively and deliberately manufacturing waste on purpose, as a business strategy. Large Language Models are the most recent iteration of this business model, squandering a years' worth of supercomputer power to train a chatbot to regurgitate slop. Before them was the crypto cultists, literally burning coal to try and solve math problems for digital tokens; before them, it was (and still is) "Big Data", demanding invasive surveillance of every person, action, click, scroll, tap, movement, word, blink, and payment, hoovering up storage capacity for no discernible benefit.

Okay, perhaps that's a bit hyperbolic. See, all of the above do have some benefit to their founders, their investors, and a minuscule number of organizations that aren't Nation States. All of those technologies (barring LLMs) are what I would normally lump into "High Performance Compute" applications, realms previously barred to all but the biggest of the big players: megabanks, insurance companies, national governments, and the like. These functions required substantial investment in infrastructure and compute on the order of tens of millions of dollars, teams of experts to wrangle cutting-edge hardware and niche software, pushing the boundaries of technology in the process to ensure the modern world could continue to function.

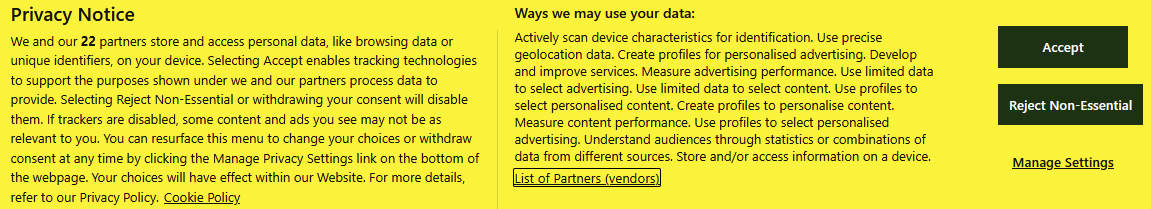

With public cloud and managed services, suddenly these applications became available to substantially more organizations - namely advertisers and data brokers. This is where I'd generally mark the "start" of the shift to a waste-production technology industry, as fad after fad was shoved down the throats of businesses with the claim that they would bring billions in returns and a transformation of how work is done. What started initially as gathering site metrics through cookies ballooned into invasive trackers and hidden pixels, the scope of which is only recently being revealed thanks to EU legislation around privacy.

As businesses rushed to add more technologies to their portfolios, spend exploded - and remember, questioning spend is bad in the West, so nobody was really raising alarm bells while cash was flowing like water. Estate sizes exploded in public clouds, along with the associated bills. All of it was necessary according to the business, but few could detail why it was necessary, what value it provided to its operations or revenue streams. Businesses harvested gobs of data on the promise the associated patterns would juice their revenue, and that machine learning could optimize rent extraction, ignorant of the glut of waste they created in the pursuit of such objectives.

See, when Big Data and HPC were the exclusive realm of the biggest-of-the-big, there was a degree of restraint exercised in their use. Collected data had to be of immediate value, not theoretical value, because storage wasn't cheap and space was finite. Brilliant people put in serious work to identify important data points and how to collect them, how to suss out critical patterns, and how to automate action upon them. When these technologies became commoditized and accessible, it meant that bad actors could utilize them for more novel and malicious means. With Big Data, it meant mass surveillance; with cryptocurrency, it was money laundering and fraud; with LLMs, it's copyright infringement, slop-generation, and societal instability.

Waste as a Service

All of these thrive on the generation of waste as a product, at a fundamental level. The deliberate manufacturing of more data, of questionable at best value, for the sake of a lofty, far-off promise of glory and wealth. Most organizations won't ever succeed in capitalizing on it, and those that do often do so via highly invasive and exploitative business models that should be heavily regulated, if not made outright illegal.

For the technology industry, though, nobody wants to raise that particular flag with customers or regulators. Why bother showing everyone the cost of doing business when you're the one making money from everyone else's unforced errors? Thus the entire industry has shifted to what I dub the WaaS model, or "Waste as a Service": more compute, more storage, more bandwidth, more services to replace what you used for no real good reason or advantage other than generating additional spend. We see it in public cloud service providers making it nigh impossible to escape without significant egress fees, we see it in subscription-based apps and services running on rented infrastructure elsewhere for what used to be a perpetual license you ran on your local computer. We see it in the promise of "unlimited" plans for backups, for data storage, for bandwidth, for capacity.

Author's Note: I am emphatically not advocating to a return to bandwidth caps, but it's worth noting that we used to be far more judicious in the data that left our network back when limits were in place. It's also worth noting that ISPs continue actively pursuing bandwidth caps, so we must be nuanced in our discussion of technological detritus to avoid harming consumers.

A personal pain point for me is iCloud. Photos used to be stored locally on my Mac, and backed up with Backblaze. The iPhone Photo Roll used to be excluded from the iCloud storage total. This meant that waste was compartmentalized, much like how home waste has a garbage bin, a recycling bin, and a compost bin; when my photo roll was full, I'd get rid of stuff I didn't want. When Apple merged everything into a single bucket, suddenly the easier option became a $3/month subscription for a grotesque amount of remote storage. Nevermind that this made identifying actual space-hogs a gigantic pain-in-the-ass (one might suggest deliberately so), nevermind that Apple could've done more to dissuade giving them money by making it easier to cleanup stuff, no, the point was to make it easier to hoard more digital junk, and give Apple money for the privilege.

The digital equivalent of a self-storage locker, with all the "stickiness" of the customer base.

The end result is that I live as a digital garbageman of sorts, dividing my time between a career in cleaning up my employer's digital estates before being thrown out when cost savings is no longer politically useful, and spending my holidays with family helping them reclaim iPhone storage by cleaning up iCloud. I'm not alone in this cycle, either, especially in an era of subscription fatigue and declining wages relative to inflation; the struggle for cleanup is real when everything is purposely designed to accumulate, but never destroy, from the end user to the Fortune 50 Enterprise and every segment in between.

Truth be told, I'm not quite sure where to end this post. I don't really have a call to action, because I don't believe most of society actually cares about its footprint - digital, carbon, physical, or otherwise. As long as the core costs remain cheap - storage, energy, compute - and regulation remains absent, there's simply no disincentive to stop our collective hoarding problem. In an ideal world, we'd be discouraging data accumulation through stiff and serious penalties for even accidental disclosure ("You have it, you're responsible for it"), to the point no insurer in their right mind would be willing to prop up the vast hoovering going on in private enterprise. In an ideal world, we'd be designing devices and software to make it easier to manage our footprints by surfacing periodic reviews of "old" or "abandoned" content, rather than shoving a new subscription tier down our throats.

But we're not in an ideal world, and thus there are no easy answers.

Only the hard work of doing the right thing, consistently.